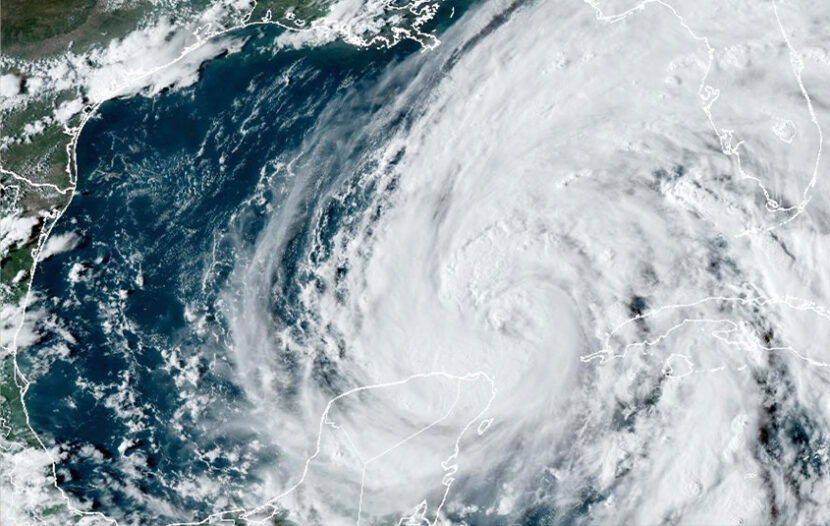

CRAWFORDVILLE, FL — Hurricane Helene roared ashore as a powerful Category 4 storm in a sparsely populated region of Florida, peeling the siding from buildings, trapping residents in rising floodwaters and knocking out power to millions of customers. At least five people were reported dead.

The storm made landfall late Thursday with maximum sustained winds of 140 mph (225 kph) in the rural Big Bend area, home to fishing villages and vacation hideaways where Florida’s Panhandle and peninsula meet.

A person looks over a flooded street due to Hurricane Helene late Thursday, Sept. 26, 2024 in New Port Richey, Fla. (Danielle Molisee via AP)

Video on social media sites showed sheets of rain coming down and siding coming off buildings in Perry, Florida, near where the storm arrived. One local news station showed a home that was overturned.

First responders were out in boats early Friday to rescue people trapped by flooding in Citrus County, some 120 miles (193 kilometers) south of Perry.

“If you are trapped and need help please call for rescuers – DO NOT TRY TO TREAD FLOODWATERS YOURSELF,” the sheriff’s office warned in a Facebook post. Authorities said the water could contain live wires, sewage, sharp objects and other debris.

Nearly 4 million homes and businesses were without power Friday morning in Florida, Georgia and South Carolina, according to poweroutage.us, which tracks utility reports.

One person was killed in Florida when a sign fell on their car, and two people were reported killed in a possible tornado in south Georgia as the storm approached. Trees that toppled onto homes were blamed for deaths in Charlotte, North Carolina, and Anderson County, South Carolina.

The hurricane came ashore near the mouth of the Aucilla River on Florida’s Gulf Coast. That location was only about 20 miles (32 kilometers) northwest of where Hurricane Idalia hit last year at nearly the same ferocity and caused widespread damage.

As the hurricane’s eye passed near Valdosta, Georgia, a city of 55,000 near the Florida line, dozens of people huddled early Friday in a darkened hotel lobby. The wind whistled and howled outside.

Electricity was out, with hallway emergency lights, flashlights and cellphones providing the only illumination. Water dripped from light fixtures in the lobby dining area, and roof debris fell to the ground outside.

Fermin Herrera, 20, his wife and their 2-month-old daughter left their room on the top floor of the hotel, where they took shelter because they were concerned about trees falling on their Valdosta home.

“We heard some rumbling,” said Herrera, cradling the sleeping baby in a downstairs hallway. “We didn’t see anything at first. After a while the intensity picked up. It looked like a gutter that was banging against our window. So we made a decision to leave.”

In Thomas County, Georgia, where residents had been under a curfew, the sheriff’s office said it was extended until noon Friday.

“This curfew helps protect first responders and citizens of our community as conditions are still very hazardous. Please shelter in place,” the office posted online.

Helene is the third storm to strike the city in just over a year. Tropical Storm Debby blacked out power to thousands in August, while Hurricane Idalia damaged an estimated 1,000 homes in Valdosta and surrounding Lowndes County a year ago.

“I feel like a lot of us know what to do now,” Herrera said. “We’ve seen some storms and grown some thicker skins.”

Soon after it crossed over land, Helene weakened to a tropical storm, with its maximum sustained winds falling to 70 mph (110 kph). At 5 a.m., the storm was about 40 miles (65 kilometers) east of Macon, Georgia, and about 100 miles (165 kilometers) southeast of Atlanta, moving north at 30 mph (48 kph), the National Hurricane Center in Miami reported.

Forecasters expected the system to continue weakening as it moves into Tennessee and Kentucky and drops heavy rain over the Appalachian Mountains, with the risk of mudslides and flash flooding.

Even before landfall, the storm’s wrath was felt widely, with sustained tropical storm-force winds and hurricane-force gusts along Florida’s west coast. Water lapped over a road in Siesta Key near Sarasota and covered some intersections in St. Pete Beach. Lumber and other debris from a fire in Cedar Key a week ago crashed ashore in the rising water.

Beyond Florida, up to 10 inches (25 centimeters) of rain had fallen in the North Carolina mountains, with up to 14 inches (36 centimeters) more possible before the deluge ends, setting the stage for flooding that forecasters warned could be worse than anything seen in the past century.

“Please write your name, birthday, and important information on your arm or leg in a PERMANENT MARKER so that you can be identified and family notified,” the sheriff’s office in mostly rural Taylor County warned those who chose not to evacuate in a Facebook post, the dire advice similar to what other officials have dolled out during past hurricanes.

School districts and multiple universities canceled classes. Airports in Tampa, Tallahassee and Clearwater were closed Thursday, while cancellations were widespread elsewhere in Florida and beyond.

A day before hitting the U.S., Helene swamped parts of Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, flooding streets and toppling trees as it brushed the resort city of Cancun and passed offshore. In western Cuba, Helene knocked out power to more than 200,000 homes and businesses as it brushed past the island.

At one point, forecasters feared that hurricane conditions could extend as far as 100 miles (160 kilometers) north of the Georgia-Florida line. Overnight curfews were imposed in many cities and counties in south Georgia.

“This is one of the biggest storms we’ve ever had,” Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp said.

For Atlanta, Helene could be the worst strike on a major Southern inland city in 35 years, said University of Georgia meteorology professor Marshall Shepherd.

Helene is the eighth named storm of the Atlantic hurricane season, which began June 1. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has predicted an above-average Atlantic hurricane season this year because of record-warm ocean temperatures.